Fortunately, developing a casual understanding of art is not all that difficult. It is true that some people devote their entire lives to studying the minutest details of an artists’ work, but there’s no need to become an expert to have a meaningful relationship with art. All it takes is a moderate attention to detail, a little bit of patience, and a willingness to reflect on your own feelings. Here, I’ll show you a quick way to approach and appreciate a painting, although the ideas here can be applied to works in other mediums (sculpture, drawing, even architecture and fashion) quite easily. There’s no shortcut to understanding I can give; great art rewards the hundredth viewing as much as he first, and you can spend a lifetime pondering the decisions an artist made in one painting. Instead, I’ll try to give you a process to follow that will help you get the most out of a painting the first time you see it. While I’m on the subject, a word about “great art”. Andy Warhol said that if you want to tell a good painting from a bad one, first look at a thousand paintings. There are no hard and fast rules about what makes a piece great, mediocre, or bad; remember, Van Gogh’s work was once considered amateurish and forgettable. There are, of course, standards that matter within the professional art world, but you don’t owe the professionals anything, so don’t worry too much about what they think qualifies as “great”.

Take a Look

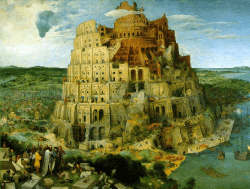

Art should appeal to you first through your senses. That doesn’t mean a painting has to be beautiful to be good, but it must grab your eye in some way. Give a work a moment to do its thing — some works are intriguing in subtle ways. A work might grab your attention through its subject matter, it’s use of color, an interesting juxtaposition of objects, it’s realistic appearance, a visual joke, or any number of other factors. Once you’ve gotten an overall look at the painting, ask yourself “what’s this a picture of?” That is, what is the subject of the painting? The subject might be a landscape, a person or group of people, a scene from a story, a building or city scene, an animal, a still life (a collection of everyday items like a bowl of fruit, a pile of books, or a set of tools), a fantasy scene, and so on. Some paintings won’t have a subject — much of the work of the 20th century is abstract, playing with form and color and even the quality of the paint rather than representing reality. The painting above, by the Dutch artist Breughel, represents the Tower of Babel. Scenes from the Bible or from classical mythology are popular in older work; since the end of the 19th century, scenes of everyday life have become more common. If you know the story, you’re one step ahead of the game, but it’s possible to enjoy the work without knowing the story it illustrates.

What’s That All About?

Look for symbols. A symbol, very simply, is something that means something else. The Tower of Babel is a well-known symbol in Western society, representing both the dangers of pride and the disruption of human unity. Often a painting will include very clear symbols — skulls, for instance, were often included in portraits of the wealthy to remind them that their wealth was only worldly and, in the grand scheme of things, ultimately meaningless. But just as often the symbolism is unique, the artist’s own individual statement. Don’t get caught in the trap of trying to figure out “what the artist meant”; focus instead on what the work says to you.

How’d They Do That?

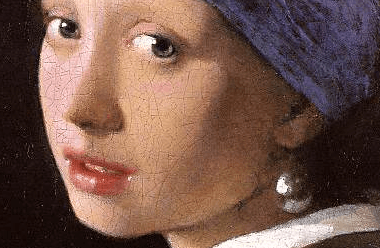

The next consideration is style, which is essentially the mark of the artist’s individual creativity on the canvas. Some artists follow well-established styles — many Renaissance portraits look almost exactly alike to the casual viewer, for instance — while others go out of their way to be different and challenging. Some artists create closely detailed, finely controlled works, others slap paint around almost haphazardly creating a wild, ecstatic effect. It may not seem as obvious as the subject and symbolism, but style can also convey meaning to a viewer. For example, Jackson Pollock’s famous drip paintings convey the motion and freedom of the artist in the act of creation, despite being completely abstract. Vermeer’s Milkmaid, on the other hand, is notable for it’s incredibly fine detail and careful application of thin glazes of oil paints (which doesn’t come across in a photograph, alas) which create a luminous quality, imparting a kind of nobility and even divinity to the simple act of a servant pouring milk.

My Kid Could Do That!

A large part of the appeal of art is emotional — some artists go out of their way to inspire strong reactions ranging from awe and lust to anger and disgust. It’s easy to dismiss work that upsets our notion of what art could be, and any visitor to a gallery of modern art is likely to overhear at least one person complaining that “any three-year old with a box of crayons could do that!” Knowing that an artist may be deliberately evoking an emotional response, it pays to take a moment and question our immediate reactions. If a work makes you angry, ask yourself why. What is it about the work that upsets you? What purpose might the artist have in upsetting you? Likewise, if your feelings are positive, why are they positive? What about the painting makes you happy? And so on — take the time to examine your own emotions in the presence of the painting. This is by no means a complete introduction to art, let alone a complete course, but it should help get you started in appreciating art. The more you know, the better the experience will become, but you don’t need to know much to get at least something out of a painting. Keep in mind these 4 concepts (I’m trying not to call them the “Four Esses”) — subject, symbolism, style, and self-examination — and pay a visit to your local art museum or gallery and see if you don’t find something worth your time. Artwork courtesy of Nicholas Pioch’s WebMuseum.